The Redevelopment Imperative

Read full article

CW Gold Benefits

- Weekly Industry Updates

- Industry Feature Stories

- Premium Newsletter Access

- Building Material Prices (weekly) + trends/analysis

- Best Stories from our sister publications - Indian Cement Review, Equipment India, Infrastructure Today

- Sector focused Research Reports

- Sector Wise Updates (infrastructure, cement, equipment & construction) + trend analysis

- Exclusive text & video interviews

- Digital Delivery

- Financial Data for publically listed companies + Analysis

- Preconceptual Projects in the pipeline PAN India

Casagrand Launches Keystone In Tiruppur

Casagrand has launched Casagrand Keystone, a gated residential development at Rakkiyapalayam, off Avinashi Road, in Tiruppur. Spread across 2.2 acres, the B+G+5 structure comprises 142 units of 2 and 3 BHK homes, supported by 48 indoor and outdoor amenities. The project is introduced at a starting price of Rs 5,199 per sq. ft. The development allocates 1.3 acres to open space, including a central park of about 24,500 sq. ft. A 6,800 sq. ft. clubhouse includes a multipurpose hall, mini theatre and indoor recreation facilities. Other amenities include a 5,100 sq. ft. swimming pool, poolside par..

Premium homes account for half of India’s housing sales in 2025

Knight Frank India, in its latest report on India’s office and residential property market, has highlighted a significant shift in housing demand, with homes priced above Rs 10 million accounting for 50 per cent of total residential sales across the top eight cities in 2025. The findings underscore the growing dominance of premium housing in the country’s real estate landscape.Out of 348,247 residential units sold during the year, approximately 175,091 units were in the Rs 10 million-plus category, marking a 14 per cent year-on-year increase. The data reflects changing buyer preferences, w..

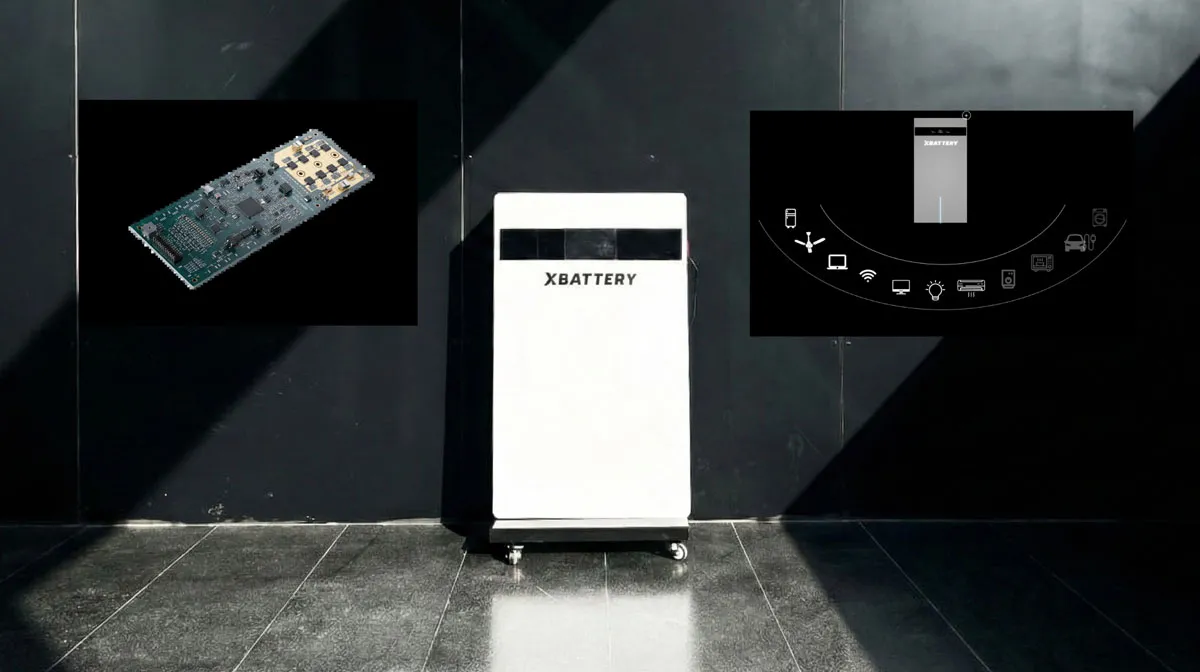

Xbattery launches XB-5K energy storage system for homes, offices

Xbattery, a Hyderabad-based deep-tech company specialising in next-generation energy storage and battery management technologies, has introduced its flagship XB-5K, a scalable 5kWh energy storage system designed for homes and offices in India.The XB-5K is built on the company’s indigenously developed BharatBMS platform, described as India’s first universal high-voltage battery management system architecture aimed at reducing import dependence and improving after-sales service capabilities. The launch comes as India seeks to strengthen domestic manufacturing and address reliance on imported..