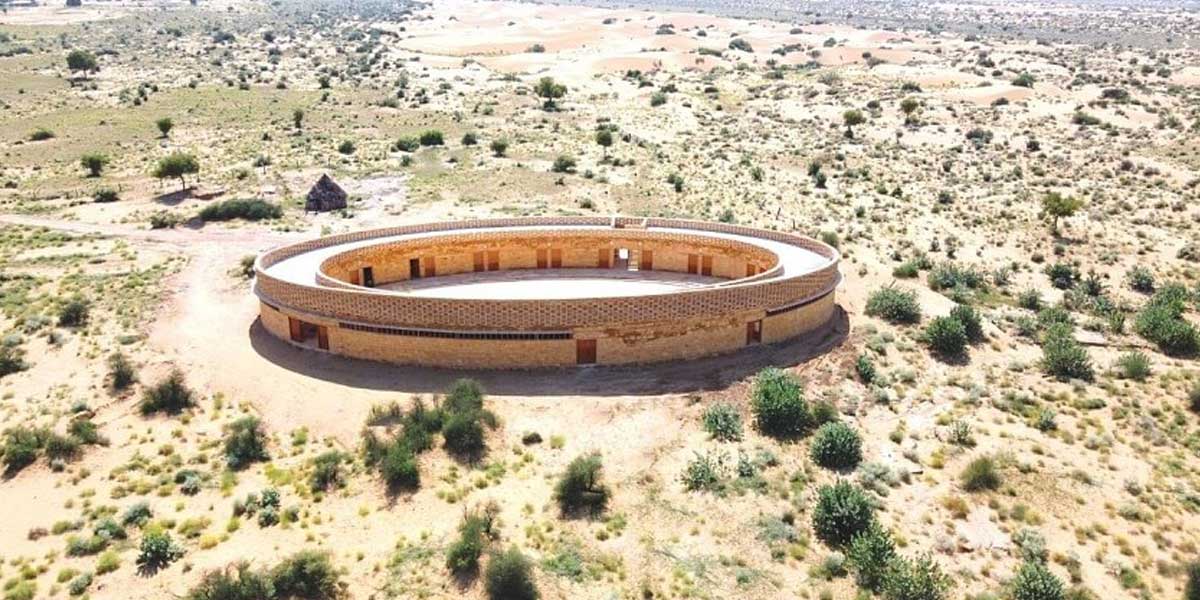

An architectural marvel, the Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls’ School conceptualised by CITTA founder Michael Daube, and designed by US-based architect Diana Kellogg made of yellow sandstone stands in the middle of the Thar desert.

The location and structure

Situated amidst the sand dunes, a six-minute drive from Jaisalmer into the Kanoi village stands this oval structure marvel - The Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls’ School. Made of yellow sandstone, this structure has no air conditioners installed in it and yet allows students to study and play without being bothered by the harsh weather conditions.

The school portion of this structure, known as the Gyaan Centre, will accommodate 400 girls from kindergarten to Class X. The complex also has a textile museum and performance hall, as well as an exhibition space for artisans to sell their crafts. In another building, women will be trained in traditional arts like weaving and textiles to preserve dying handicrafts.

It took a decade for Michael Daube, founder of CITTA, a non-profit organisation, to conceptualise the building, and help it materialise. Michael roped in US-based architect Diana Kellogg, who conceived the design.

The architect says the oval shape kept coming up in her initial drawings, and that is how the ellipse structure was finalised. She adds that the shape also made practical sense, as it would reduce the distance between the different sections in the building. Having a courtyard for the building was familiar to Indian culture.

The inner walls of the building are plastered with lime, which insulates the building. The local sandstone has been used for construction, which provides protection from extreme heat during the day, and warmth during evening hours. To allow enough room for ventilation and make the classrooms and other offices bigger in size, drawings of the structure were revised multiple times. drawings to make

Sustainability in the dessert

Diana travelled to India in 2014 and saw how life in the desert was thriving. “I have never worked outside New York, and it was difficult to comprehend building a project in the middle of the desert. But upon my visit here, I saw the beautiful buildings, music and art of Rajasthan. Even the step-wells here are an architectural wonder. The experience gave me the confidence that this project could be made,” she says.

She says the inspiration to design the building with elements of sustainability came from the surroundings. “I did not want to impose or incorporate any western ideas. I met people from nearby villages to understand the culture of the state. I observed the fluid characteristics of dunes, and in them, saw many symbols of womanhood,” she adds.

The elliptical shape of the structure helps bring aspects of sustainability. “The canopy and the jalis filter the sand. They keep the sun and heat out. The pattern of airflow inside the building naturally cools it down,” she says. She adds that using local material to create the infrastructure helped reduce carbon emissions. “There are talented artisans in every village surrounding the school, and there could not be a better material to use than sandstone,” she says, adding that this helped reduce the carbon footprint from transportation and logistics.

The solar panels on top of the building work as a canopy and provide shade while simultaneously powering the building. A cooling system uses geothermal energy at night to cool the building during the day.

A contractor fit for the job

Kareem Khan takes special pride in this particular piece of work. “Many contractors rejected the offer as it seemed unfeasible, and they feared incurring losses. I came to know about the project through a friend, who told me that one non-profit organisation had been trying to make this work for the past 10-15 years, but had not found the right expertise. I was confident I could make it work and accepted the offer,”. Also being an expert in heritage structures, he says the only challenge initially takes special pride in this particular piece of work. “Many contractors rejected the offer as it seemed unfeasible, and they feared incurring losses. I came to know about the project through a friend, who told me that one non-profit organisation had been trying to make this work for the past 10-15 years, but had not found the right expertise. I was confident I could make it work and accepted the offer,” he says.

Empowering women and artisans

Describing the artisans as magicians of stonework, the architect Diana recalls an incident. “I remember an instance when we could not find the washroom sinks of the right size. The artisans carved them out of the stone. This would never happen in the US,” she says, adding that without the project, she would have never got the opportunity to work with cut stone.

Michael says he decided to build the school in Jaisalmer considering the disturbingly low literacy rate and a high dropout rate of schoolgirls in the state. “The girls are in dire need of support. More women need to be empowered and educating them is the only solution,” he adds. The logo made for the school symbolises healthcare, women empowerment and education, which Michael says are crucial aspects to nurture and allow women to hold a powerful place in the world. He says he wanted to build a monumental school where parents would feel proud to send their daughters to study.

Support from royals and the community

The creators of this school reminisce that it took time to convince royals, politicians, celebrities and stakeholders to be a part of the cause. They spent years finding the right opportunity to get all stakeholders in place. To gain community support, Michael percolated the idea of tourism, culture, craftsmanship and other unique aspects of Jaisalmer. “I did not want the building to function only as a school. Hence, a beautiful structure that represented womanhood was needed. Besides being an education centre, the school will attract tourists and serve as a global platform to host events for women empowerment and global programmes like Ted talks,” he explains.

The school could not open in 2020 owing to Covid conditions but the creators are hopeful that the functioning will start soon as the pandemic situation subsides.